On the Green Line

The village of Hmoud sits in a relaxed posture on the western side of a small ravine. Sloping gently eastward, this village occupies the edge of a vast wheat plateau that stretches with its red soil towards the west till it falls suddenly into rugged landscape overlooking the Dead Sea. To the north of Hmoud, towards the village of Smakieh, the ravine gets deeper, with stiffer sides, and heads north until it meets the dramatic canyon of Wadi Al Mujib.

Hmoud is part of a line of villages that are said to have been placed in this location for a specific function: To protect the wheat land from Bedouins’ raids coming from the marginal lands to the east. This location is on the green line, the eastern border of the Moab Plateau. Hmoud is part of the line of villages that run north-south, a line that can be seen as marking, traditionally, the end of the semi-nomadic agricultural land and the beginning of the Bedouin land.

In this location, the traditional inhabitants of the village were seminomadic; they seasonally cultivated the fertile land to the west and spent the summer as nomadic herders, in Bedouin tents, away from their village in all directions. This village was built by one Christian clan, Al Halasa, during the early 1900s, and kept its pure Christian population until the 1970s. In this village you can find the last traces of a strange combination, not found anywhere else, and now rare even in Jordan; the Christian Bedouins.

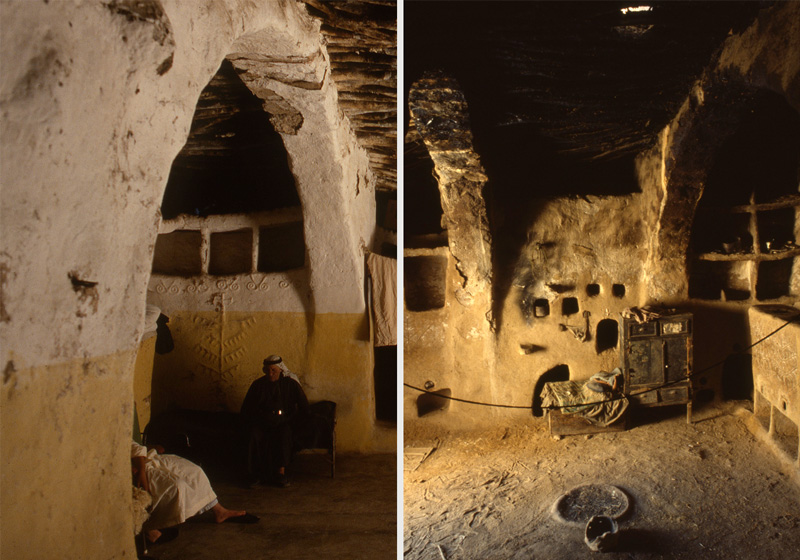

Many of the traditional houses of Hmoud were built on caves that used to be a strong attraction for settling this site, as they provided early shelters prior to the advent of construction. The village reads as a one-piece complex, made of cubes that are similar in size and orientation. Walls are randomly spotted with black basalt stone, and in few elevations rows of basalt are alternated with rows of white limestone. The mixture of the two kinds of stone appears like colors in Karak grain sacks woven of white wool and black goat hair. Traditionally all houses were of one floor, with roofs of mud resting on oleander branches or tree trunks that span between stone arches. Only one traditional house built in 1921 had two floors.

Looking at the village from the west gives a different impression than looking at it from the east. The western view is clearer, and the sharp contrast between the black and the white stones gives it a poignant vividness, while the eastern view is monochromatically muddy. The rain comes every winter, brought by westerly winds, to wash the village walls facing west, while the walls facing east have been accumulating dust for the last hundred years.

Hmoud offers some of the most impressive examples of the 'traditional Jordanian' house, which had, until the mid-80s, a stunning collection of mud furniture. The portable mud pieces, as well as the built-in shelves and wheat silos, were richly decorated with crosses and abstractions of plants.

Today traditional Hmoud, or whatever is left of it, might still present the last chance to preserve an important element of Jordan’s cultural heritage.

There are tens of villages around Karak, most still have some traditional architecture and some have impressive surprises of natural or cultural heritage. The village of Hmoud represents a good destination for seeing examples of Jordan’s traditional village architecture. Hmoud is about 15km to the northeast of Karak, and only 5km east of the King's Road. From the towns of Rubba or Qasr, you can find paved sideroads heading east to connect to Smakieh, Hmoud and Adir. The Karak plateau and its villages is a full day destination, Hmoud can be combined with visiting other villages in the surrounding area, and a tour of the Karak Castle and the historic marketplace of Karak. If you are driving on the King's Road, the view from both sides of Wadi al Mujib is worth stopping for.